- Home

- Resurrection ▾

-

Learn ▾

- Free library

- Glossary

- Documents

- Initiation

-

Shaped fabrics

- Introduction

- Popularization

- Definitions

- Le métier de façonné

- Principes du façonné

- Mécaniques de façonné

- Le jeu des crochets

- Les cartons

- Chaîne des cartons

- Mécanique 104 en détail

- Pour en finir

- Montage façonné

- Empoutage 1/3

- Empoutage 2/3

- Empoutage 3/3

- Punching, hanging and dip

- Autres façonnés

- Façonnés et Islam

-

Cours de tissage 1912

- Bâti d'un métier

- Le rouleau arrière

- Les bascules

- Formation du pas

- Position de organes

- Mécanique 104 Jacquard

- Fonctionnement 104

- Lisage des cartons

- Le battant du métier

- Le régulateur

- Réduction et régulateur

- Mise au métier d'une chaîne

- Mise en route du métier

- Navettes à soie

- Battage

- Ourdissage mécanique

- Préparation chaînes et trames

- Equipment ▾

- Chronicles ▾

- Fabrics ▾

- Techniques ▾

- Culture ▾

- Language ▾

Gendarme, Switzerland, Army Soldier, Thumbtack, Cherche-midi,These are the names most commonly used to designateThe Pyrrhocoris Apterus, in other words the bug with the body of fire.

More ...

Many years later, in 1981, I found my devil's little friends at the foot of the wall of the house we had just bought in Auvergne to set up our Lyon business and where we still live today. It was a real shock to me. I had forgotten them and by the fruit of chance, I had never been given to see others during all these years ... In 2003, they are still there. I love in those early days of September, come to observe them by sitting beside them, under the trees, as I did child, in the warm rays of the noon sun of those beautiful late summer days. So, for me, during these few moments, the loop and curl and I calm down ...

Back in La Croix-Rousse, in September 1978, Bernard tassinari, my new boss, provides me with a function housing. It was an apartment built into the building of the old Tassinari workshop, located at Montée Kubler, in Croix-Rousse. For Lyon, climb Kubler is the small street parallel to the street Richan where is the studio of Mr. Mattelon, great figure Lyon if it was ...

Great apartment for the 25 year old single bachelor that I was. On two levels, with a large terrace adjoining the sawtooth roof of the factory. For at Tassinari & Chatel, the name of Usine or Meca was given pompously to this mechanical workshop, to differentiate it from the workshop of the handcrafts that I was going to integrate soon, located two steps away, rue Coste, between The Croix-Rousse and Cuire. I would go to the Coste street shop on foot, it's about 6 or 7 minutes, sometimes passing by a traboule joining the old hall of the festivities of the Loop. This little known path is lined with small gardens well hidden. There was one of those many terrains of boules of quarter where the effigy in enamelled sheet of Fanny was displayed, showing its pretty fleshy buttocks that the unfortunate (or blessed?) Loser of the party had to embrace under the mockery and the jeers of the others players.

Bernard Tassinari came to visit Montée Kubler on my arrival. Before joining the Canuts de la Coste, I had to leave for three months to take a theoretical and practical training course on mechanical weaving at the Voiron Weaving School (which of course has closed its doors since then). This obligatory passage was not really essential, but allowed Bernard to benefit from state aid for the employment of young people under the age of 27, which was just my case. Wishing me a good stay at Voiron, Bernard Tassinari took leave of me, while handing me an envelope which seemed to me very intriguing. In this envelope, a bundle of banknotes corresponds almost to one month's salary. Bernard renewed the thing during the 3 months of the formation. If I relate this detail, it is to make clear that the silky Lyonnais have long had the reputation often not usurped exploiters and blinds. Nothing compelled Bernard Tassinari to make this generous gesture, in fact, unexpected in the profession. Needless to say how immediately this man seemed to me sympathetic !!! And this lasted all the time we worked for him. If we have not made a fortune, we also do not feel that we have been seriously exploited. Thanks to Henri and Bernard ...

Ah, Meca, Meca ... the mechanical weaving workshop of Tassinari, above which I lodged ...I had access to a large key which allowed to enter the workshop by the heavy solid wood door giving Montée Kubler. Sometimes, even though I did not have an explicit authorization to do so, I sometimes got there on the stroke of midnight. A pure happiness. Paradise, if it exists must certainly look a bit like this!The rows of old mechanical looms, Diederichs and others, lined up, silent, resting for the night. Entering the workshop, with all the respect due to these old machines providing every day efforts for decades, I lit a few lamps, here and there, according to my progression between the machines . The space was filled everywhere. Materials, coils and pugs, Jacquard designs, spare parts, piled on shelves, boxes, boxes ...

It was pure happiness and I stayed there for a few minutes to breathe the smell mixed with silk and grease, to rewind ...

By day, Meca was a strangely calm and noisy hive at the same time. As you passed the large solid wooden door, a deafening noise assailed you suddenly. Yet, in spite of this noise, a great calm reigned. The workers in the trades each had an old straw chair or a wooden stool. Installed near their craft, they almost all read "Nous deux" ...

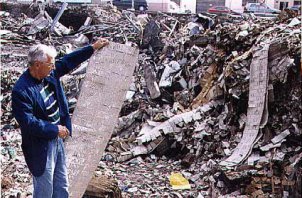

Look at what they did with Meka ...

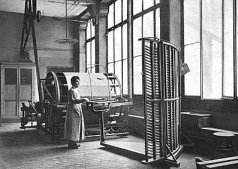

Horizontal warper Diederichs end XIX ° / early XX °

Sometimes we would pick up our channels directly from Madame Martinez, when Michel had not had time to recover them. It was the opportunity to meet her and trim the bib (to discuss in jargon Lyonnais). One could feel how hard the work was and the difficult life to win. We felt that this activity she led and which she led with talent had not really been the subject of a free choice ...

In 1981, we had to leave the old farm that we lived in and that did not belong to us to find another housing and workshop. We bought a 300 m2 old school on three floors and set up our workshop on the top floor.

We woven kilometers of velvet and satin grigné for Tassinari & Chatel between 1978 and 1987. Then we stopped this activity to turn the page definitively and we separated from all our tools.

But is a page ever turned definitively?

The Henry's calculating machine ...

Henri calculated the sum he had to give us for the production of our footage. A price per meter was fixed and increased several times a year. Henri took a hidden pleasure in using his extraordinary calculating machine. Nothing but this spectacle was worth the trip of Auvergne ...

Then Henri went to the office. He returned a few moments later, accompanied by Bernard Tassinari, who brought us, ruby on the nail, the check he had just signed. There was usually a more or less lengthy conversation about business, the conjuncture and privacy.

We took leave, wealthy and relieved that everything went well.But before returning to the Auvergne, we made a detour mounted Kubler to the mechanical workshop.

In the workshop, we found Michel who had at our disposal any new chain rolls and weft bobbins. The warping was done a few yards from here, in the warping workshop of Madame Martinez, who stopped working a few years ago to enjoy the joys of retirement. Madame Martinez liked us very well, and we returned it to her. This amazed him and amused him to see that we had chosen this moribund activity of weaving by hand, especially after leaving university studies. She could not get over it and nagged me gently every time she saw me. She worked with several workers and had several modern warping machines, but I was fascinated by the old warper Diederichs, which she used mainly for hand-craft chains, with the period crew with 400 pugs, as we know Sees on the picture and like the one we found for our workshop.

Tool for measuring the piece of fabric

Then the fabric was visited, ie unrolled and rewound on another roll 2 or 3 meters apart, under the light. Henri watched the fabric in search of possible defects. If a big fault occurred, it was marked with a bell, a piece of wire fixed in the edge of the fabric at the height of the defect.

In principle, a serious default involved a withholding of money on the way price. In eight years we have had some miseries. It must be admitted that no penalty or detention of money was ever applied to us.

The fabric visited and measured, Henri rejoined his desk on which stood an ancient machine to calculate quite astonishing and impractical which required an incredible number of manipulations and turns of crank to execute the least operation. Henri seemed to hold this instrument as the apple of his eyes and I suspect him, who is now retired, to have spent his whole career with this machine ...

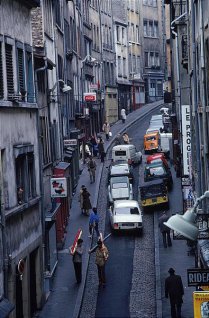

Between Center ville and Croix-Rousse in the 70's.Look at the sign of Cep Vermeil with the image of Gnafron,One of the two big reds that stained Lyonnais with Kiravi ...

And it was, each time the same ritual that thousands of canuts lived for several centuries. The Headquarters of the Maison Tassinari and Chatel was also an extraordinary place, which remained the same for centuries. Located on a floor in an old bourgeois building, it was silent and cozy. An imposing surface whose floor was covered with an old waxed oak parquet, assembled with broken sticks, if I remember correctly. Everywhere, fabric shelves and large banks of silk, oak or other hardwood. Everywhere, wood and cloth. The floor cracked at every step and the fabrics dampened all the noises. Employees, secretaries and accountants, managed and invoiced in an office at one end. Nowhere is there any concession to modernism. All this was very impressive because bearer of a long historical past of exactly 323 years.

In the middle of the banks and fabrics, there was the office of Henri Gazanion, the head of department who had made me enter the silk factory in 1979.

It was he whom we came to see ...

After the customary politeness, it was practiced the measurement of the length of the cuts, using the traditional meter of silk.

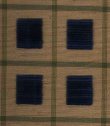

The velvet craft gridded in 1980.

At the rhythmic rhythm of twinned mechanics, the prestigious gold, silver and silk brocades are produced at a rate of a few centimeters per day. The superb brooches with innumerable colors, lampas with satin bottom and patterns thrown, wind imperceptibly on the rollers.

In the studio with the bumpy patched floor, the sun darts its rays on the sheets of threads in the colors of rainbow. And these traits of light are spread out in a pool of light, incapable that they are to pierce the silken sheet whose density often reaches 130 threads to the centimeter.

In winter, at nightfall, the workshop takes on a supernatural dimension. In the sanctuary of the silk, only the individual lamps of the crafts shine, which replaced the smoky old-fashioned chelus. It is a fascinating spectacle, like that of the silk chains and the conspicuous face of the canut leaning on its clapper, which alone emerge from total darkness.

In December 1979, having met my future wife living in the Auvergne, I left the workshop of Rue Coste. Bernard Tassinari proposed to me to take a loom and take charge of the production of gridded velvet. I was delighted because I had no other perspective of work.

The building of the trade in question had been stored for ages in a room under glass of the street Calas. This large warehouse, disappeared since, was empty apart from this building. The canopy, largely damaged for a long time, allowed the many pigeons of the neighborhood to come and take refuge there and breed. So I spent several days to extract and clean the various pieces of the craft, drowned in 20 cm of pigeon guano. Twenty-five years later, I still smell in my nose!

Married in December 1979 in Craponne sur Arzon, in the Haute Loire (43), we were initially settled in an old farm. Very quickly, I asked the Tassinari House if she would not have another fabric to give me in making. Because I had restarted other hand looms. Tassinari confided to us a satin grigné in 140 cm of width. Too heavy to handle for Claire, I had to give him my job of velvet and inherit the craft of satin grigné.

So we had an independent status as a craftsman, and a unique client, Tassinari. It provides us with full-time work between 1980 and 1988, when we ceased our activity.

The weaver only dealt with weaving. Tassinari provided us with the chain all ready on our roll, and the whole weave unwound on reels. It is up to us to carry out the tasks of resetting, punching and twisting the chains on the loom.

Each month, we went down to Lyon, at the head office, which we called the store, to bring a cup of 30 to 50 meters of our two fabrics. The shop was located on the slopes of La Croix-Rousse between the Terreaux and the Plateau.

We wove this velvet for many years in different colors. He had something odd about him. It was the contradiction between the very irregular doping weft and the velvet which, on the contrary, is generally characterized by its regularity. There was something very unpleasant when the shuttle dropped a portion of very flamed dollop in the middle of a square of velvet, massacring irreparably this square, to the delight of Tassinari and his customers who bought it for this feature. We have never been able to do that. We wove this velvet for nearly 10 years, and have loved and hated it in turn ...

Practically, only one person strolled through the aisles, often an oil burette in his hand. Michel, the stationer and workshop manager was a particularly nice person. Calm, soft voice, timid air, as hidden behind his slightly red beard in the shape of a necklace, it was the key to vault of the building without which everything would have collapsed.

A colorful character, known to all in the neighborhood was Pierrot, said Pierrot the pipe. He had long been responsible for many services between Meca and the Headquarters of the Tassinari House. He was often crossed in the streets of the Croix-Rousse, pushing his little cart equipped with two bicycle wheels. He would take a piece of cloth, some materials or drawings, from one place to another. Pierre Laffont, known as Pierrot la Pipe, was a Croix-Roussienne figure, a celebrated man, almost a mascot ...

I did my three months internship at Voiron, without much conviction of the interest of the thing for the continuation of the events. I still found a certain pleasure in piloting the old shuttle looms, on which we wore dishwasher-cloths with materials most often supplied by the weaving mills of the corner. Then, the trainees tried to sell the cloths at low prices to the population to put a little butter in the spinach of the school ...

After returning to Lyon at the end of my training as a mechanical weaver, I finally took up my duties in rue des Coste in the handcrafts workshop.There was René, the chef d'atelier, the Best Workman of France, a forty-year-old and a canute of all time.René looked old, I was then only 26 years old. He impressed me terribly. He wore a mustache, and under a most impassive air, he sometimes gave way to a sly smile and a mocking eye. His repartees were scathing and his mind sharp. A true worthy descendant of Guignol in short.

There was still a young man of 18, a great teenager not yet finished, and Father Billonnet. At the edge of retirement, perhaps even behind the retirement age, Father Billonnet led his life as a peaceful canut. In the morning, just before he set to work, he was seated at the corner of the old De Dietrich coal-stove in dark brown enamel, reading the titles of the Progrès de Lyon, focusing in particular on the obituary in which he Found every day a deceased person whom he had known well, told us about his life, obviously taking great pleasure in observing that his peers were leaving while he remained.

Father Billonnet, an old cannon of old, knew everybody in this profession. It was a living encyclopedia of the actions and gestures of each one, and it was a treat to interrogate and listen to it. During the 12 months spent in the workshop, Father Billonnet wove a silk velvet in irons, called velvet quadrillé, string of organsin background 3 ends 20/22, chain hair organsin 2 ends 20/22 and weft doublion. This very special fabric was manufactured for ages by Tassinari. It was used to cover Empire seats. It is this fabric that Tassinari decided to give me to do when, at the end of a year, I announced to them that I was going to marry in Auvergne and that the life of an employee was not made for me. Then Father Billonnet taught me how to make this velvet, to adjust the plane, to cut the hair ...

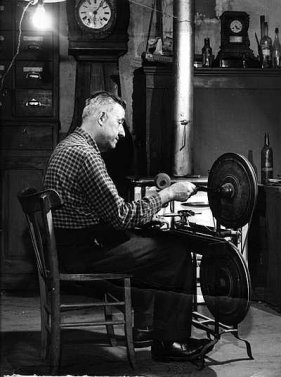

Joseph Perret in his workshop of the 2 place Marcel Bertone in the Croix-Rousse

Having left this good city of Lyon at the age of 17 years, for Savoy, then for the Mediterranean, I was training my boots a few years in law school in Aix en Provence before returning to Lyon at the age of 26 Years, determined to practice the trade of canute. I was therefore touched by my father, a childhood friend of Henri Gazanion, head of the Maison Tassinari & Chatel, the oldest silk house in Lyon. The head of department, in silk was the person in charge of manufacturing, certainly the highest position after, of course, that of the boss, in this case Bernard Tassinari.

We were then at La Croix-Rousse in September 1979. Certainly, this district had changed during my years of absence; I had known the A. Freron lemonades, whose employees were delivering the wooden boxes to the bistros in the neighborhood, using their cart in planks equipped with tires and pulled by a horse. Dung in the middle of the street.

And there were still the knife-makers who sharpened the knives and scissors on the sidewalk, the vociferating patis which emptied the granaries. And again the old UMDP tankers, which I never knew the exact meaning of, but we used to say that it meant "A M ... Plus", since this municipal odoriferous service was loaded To empty the vats of the buildings which were not yet connected to the sewer of the city.

And then on the circuit that took me from my home on rue Louis Thevenet to the private school of boys in Saint Denis, the brothers' school was located at 77 Grande Rue de la Croix-Rousse and one Annex was used at a given time in Cuire, a little further and in front of the trolley depot of the OTL (Office of transport Lyonnais), where the trolleys of lines 6 and 33 were parked for the night. Circuit, I said, which led me from my home in the Rue Louis Thevenet to the annexe of the school, to Cuire, all along the streets, the ground floor was occupied by the mechanical workshops that were looming, weaving, Wove the whole day without interruption, filling the streets of the neighborhood with a sweet melody reassuring that rocked my childhood. I picked up on the pavement the empty cones of empty silk cardboard, which were not then recorded, and I donned a magic sword which made me an invincible hero, Future promised everything.

I have just turned 50, and I have a hard time assuming that ungrateful age that I do not think I deserve. Life did not really smile at me as promised by the magic sword, even going so far as to inflict on me some tough trials of the kind that would happen. Plunged back into those memories of childhood, the child of the Croix-Rousse, I find it hard to connect with the life I lead today. Do you realize that I have known horse dung in the streets of my neighborhood, I who still have 17 years in my head ?!

Earlier still, and still smaller, I lived in my first house, an old bourgeois house in a large park which gave on the Caluire side of the 17th of Jamen Grand street and on the Chemin des grands terres (which was actually Not yet tar from everywhere). Be aware, if you know the place today. It was on the railway line where trains were still passing. One day we saw on the way a wild boar who had come even farther. I was perhaps 4 or 5 years old. I went down on the railway track and laid one of the ballast's pebbles on a rail. A kind of big pebble. I went up, very worried, to the top of the ditch, on the Chemin des grands lands, on the approach of the train, wondering if the pebble was going to derail it before it entered the station of Caluire, Remorse and eyes filled with tears. The train never derailed and each time left a pebble dust on the rail, which smelled of the gunpowder. Next to the bourgeois house, a field of cabbage cultivated by a peasant and his horse!

You can imagine that the old house no longer exists. It was razed thirty years ago to make way for a small, very small apartment building.Under the tar, there are my toys, my little chain of gold, lost, the bones of my cats, my memories and my early childhood.On the tar, there is nothing more than iridescent greasy spots left by the cars parked in the parking lot. And yet! Under this tar, I left my little friends there. These strange insects that delighted in the underbrush and with which I played so much that they marked me for life. These small insects which carry on their back a red carapace including the drawing, in black, of an African mask. I saw a devil's head and I called them my little devils. I loved them. Then I grew up, I left them, then forgotten, and covered them with tar. It's disgusting !!!

Joseph Perret filling his silk cans for the next day.

I was born in the clinic Saint-Augustin at the Croix-Rousse on April 23, 1953. This clinic has since disappeared, as many others in France.

Born of Lyonnais parents who, like most of the current Lyonnais, had parents who had immigrated from the countryside to Lyon, from the neighboring departments of Ain, Loire, Haute-Loire, Isère and Savoie.

My maternal grandfather, Aimé Perret, known as Joseph (for he did not like his first name), was the last boy in a family of fifteen children. He was born in a village in the Loire (42), neighbor of Noirétable and the country of Aimé Jacquet. Unable to take over the farm reserved for the eldest son, he had to go into exile in Lyon, in search of work, like many others at that time. Unfortunately, I do not know the details of his life, which no one thought fit to tell me, but I know that he was canut to the end. First apprentice, assuredly. Then before the war, he had a workshop of mechanical trades. After the war, he finds himself in his craft workshop (!) On the landing of his wretched apartment, at 2 Place Marcel Bertone (eg Place Belfort). That's where, little boy, I often watched him weaving or making his cans in his hand for the next day.

Joseph Perret filling his silk cans for the next day.

Joseph Perret filling his silk cans for the next day.

My checkered velvet loom in 1980.

Joseph Perret filling his silk cans for the next day.

Joseph Perret filling his silk cans for the next day.

Joseph Perret filling his silk cans for the next day.