- Home

- Resurrection ▾

-

Learn ▾

- Free library

- Glossary

- Documents

- Initiation

-

Shaped fabrics

- Introduction

- Popularization

- Definitions

- Le métier de façonné

- Principes du façonné

- Mécaniques de façonné

- Le jeu des crochets

- Les cartons

- Chaîne des cartons

- Mécanique 104 en détail

- Pour en finir

- Montage façonné

- Empoutage 1/3

- Empoutage 2/3

- Empoutage 3/3

- Punching, hanging and dip

- Autres façonnés

- Façonnés et Islam

-

Cours de tissage 1912

- Bâti d'un métier

- Le rouleau arrière

- Les bascules

- Formation du pas

- Position de organes

- Mécanique 104 Jacquard

- Fonctionnement 104

- Lisage des cartons

- Le battant du métier

- Le régulateur

- Réduction et régulateur

- Mise au métier d'une chaîne

- Mise en route du métier

- Navettes à soie

- Battage

- Ourdissage mécanique

- Préparation chaînes et trames

- Equipment ▾

- Chronicles ▾

- Fabrics ▾

- Techniques ▾

- Culture ▾

- Language ▾

From the seventeenth century, Lyon held an important place among the cities of France by the renown of its artists and the prosperity of its silk factories established by Francis I; So that a magistrate of Dijon, who visited the south of France in 1579, described with naive astonishment the incessant buzz of his manufactories, the movement of his streets, and especially the wealth of the costumes of his inhabitants.

However, in the last century, if the visitor had not entered the suburbs and was not content with an overall view and superficial judgment, he would soon have lost his way in a maze of climbing, narrow, tortuous alleys, A dirty fog, impregnated with the smoke of the machines and the ammoniacal odor of the dyeing vats.

In six-storey houses, filthy and leprous, which overlooked the street, there lived a people of pale complexion, soft flesh, of a stature generally below average, and whose size was almost always deformed by some deformity Anatomical: it was the canut. This silk worker, from whose hands came luxurious fabrics woven of gold and silver, was a true pariah. During three quarters of the day he was nailed to a craft whose exercise required the most painful body positions.

Indeed, represent the ancient weavers in the midst of these confused clumps of tools, springs, cords, pedals of all shapes and sizes, disrupting each moment; The chief workman, badly seated on a stool, waving his feet in all directions to tread the steps, raising or lowering the threads which were to form the bottom of the stuff, throwing his shuttle in the middle of these threads and those Caused one or two workmen, named lace shooters, to raise from his drawing, because they had the task of drawing strings. These unfortunate men kept the same attitude for whole days; Their limbs twisted, deformed, stumbled; And as this play, purely mechanical, required little strength, poor girls, unfortunate children, were applied to it. A great number succumbed to this barbarous craft; the others dragged on a feeble existence in too narrow, unhealthy dwellings; They did not succeed in advanced old age, and it is asserted that never a workman was a workman's grandson. It may be imagined that with such a hygiene, with such a manner of living, the intelligence of the canute was extremely limited. He was gentle, docile, his countenance was stamped with kindness and simplicity, his accent was singularly slow and dragging; But, unless there are exceptions, "said Dr. Monfalcon, who wrote the monograph on the canute," an inhabitant of Oceania possessed a greater number of ideas, and was able to combine them with greater skill. "

This sad and sad race now belongs to the legend; More sanitary dwellings, habits less contrary to hygiene, better food have made the Lyonnais weaver a robust and intelligent worker.

In 1788, 14,780 trades of all kinds were beating in the walls of Lyons; To-day, the industry of Lyons has spread, not only in its suburbs, which have become towns, but it has also gained the countryside, and it radiates on the neighboring departments.

This immense prosperity, this social transformation is due in part to a poor canon, a philanthropist without knowing it, and an unconscious mechanic, to the workman of genius Jacquard.

II

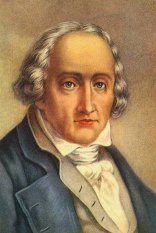

Joseph Marie Jacquard was born in Lyons on July 7, 1752. His father, Jean-Charles Jacquard, was a master worker in brocaded stuffs of gold, silver and silk; His mother, Antoinette Rive, was a reader of drawings, which consisted in indicating to the principal worker the number of black lines to which the threads of the chain must correspond in an agreed space, explaining whether it is from the background or the Fig.

His grandfather was a stonemason at Couzon, a village on the outskirts of Lyons, situated on the banks of the Saone, where quarries of a stone as red as granite are found.

Father Jacquard, who conceived no other profession for his son than his own, neglected to give him any instruction. Like Vaucansson, Jacquard, on leaving the cradle, was possessed by the instinct of mechanics. Abandoned to himself, he spent his time building wooden houses, towers, churches, and thus acquiring, without the assistance of any one, a summary instruction.

The child was barely ten when he lost his mother. This event profoundly affected his delicate and loving nature, and when his father, judging him strong enough to aid him in his work, wished to employ him to draw the lakes, that is to say, the cords which then A machine destined to form the drawing, his health could not bear the fatigues of this painful labor. His instinctive repugnance to machines which seemed to him heavy, coarse and tiring, caused him to desert his father's house. He took refuge with one of his parents, Mr Barret, a printer-bookseller, where he was employed in broaching and binding books. Then he went into the studio of Mr. Saulnier, one of the most skilful founders of print-making in Lyons. Always guided by his taste for mechanics, he made several new tools for the use of printers, which were adopted as an improvement; He devised others for the use of cutlers. At twenty, Jacquard lost his father and found himself possessed of a modest heritage. He then erected a manufactory of fabrics, and added a few workmen.

In 1778, he married Claudine Boichon, daughter of a gunsmith, a friend of his father and who was considered rich. They promised a dowry which they did not pay; Trials were instituted. Jacquard lost them. The embarrassment then entered the modest household; Soon it was misery, then ruin. Jacquard's inexperience in business, his probity, and his relentless pursuit of improvements in weaving, brought about a disaster which the envious and the enemies of the poor inventor had predicted.

At the hour of misfortune his friends abandoned him; His wife alone understood and consoled him; she was the friend of the evil days. To pay for the trials and debts of her husband, she sold the cottage at Couzon, the cradle of the family; She sold the two trades, her jewels, even her furniture. Everything passed, and Jacquard, reduced to the most frightful destitution, was obliged to leave his wife and child, to place himself in pawn at a lime-maker of the Bugey.

As for his wife, Claudine, she entered as a worker in a factory of straw hats.

In spite of the severe trials of existence, the workman was always possessed of an idea: the search for a trade suppressing the operation of the drawing of the lakes. The reading of the Science of Bonhomme Richard, which Franklin had just published, made a strong impression on his mind.

"I was sober, I became temperate," he wrote to one of his friends, "I was industrious, I became indefatigable, I was benevolent, I became just, I was tolerant, I became patient, , I tried to become a scientist. "

But the lack of money prevented him from realizing his theories, and his life would probably have passed away in sterile dreams, when the Revolution came to smooth the way for him.

This great popular movement had been ill received in the south of France. Lyons, above all, could not favorably see the emigration of the nobles, and the proscription of the rich, for his trade in silk and gold embroidery, in order to prosper, required the splendor of the court and the clergy. When, therefore, after the 10th of August, Challier, an imitator of Marat, placed himself at the head of the Jacobins and the municipality of Lyons, the sections which obeyed the royalist reaction rose, and a bloody struggle soon broke out. Challier is sent to the scaffold, and all the citizens take up arms. The city was placed in a state of defense, and an army of 20,000 men, commanded by the royalists Précy and the Marquis de Virieu, prepared, in concert with the Sardinian army, to resist the republican army of Kellermann.

Jacquard, who was then in the Bugey, ran to Lyons to share the perils of his fellow-citizens. All the heads were exalted; the young men enrolled, the women appeared near the redoubts; A military box was formed, and the insufficiency of the money was supplemented by notes from the principal merchants. The houses were crenellated; Batteries were built, artillery was melted, powder was manufactured: the population was determined to struggle with energy, and a terrible bombardment gave to the flames the richest quarters of the rebellious city: the Place Bellecour, the arsenal , The Saint-Clair quarter and the temple harbor were destroyed, while the Sardinian army was vigorously driven back into the Alps by Kellermann.

Appointed a non-commissioned officer, Jacquard fought in the advanced posts, having on his side his son, fifteen years of age. Soon abandoned to his own strength, Lyons succumbed after fifty-five days of siege. Couthon, commissioner of the Convention, made his entry at the head of the republican army, reinstated the old mountain municipality, and gave him the mission of seeking and designating the rebels, whom a popular commission was charged to judge militarily. It was then that, at his instigation, the famous decree of the Convention appeared, ordering the destruction of Lyons, and deciding that on his ruins a column bearing this inscription should be erected:

Lyon made war on Liberty, and Lyons was destroyed.

The town was to be called in the future: Commune freed.

The memories which Jacquard had retained of those terrible times were as confused as those kept by the inexperienced passenger of the tempest, where he has nearly twenty times sank. He then ran the greatest danger. People who made themselves informers, for fear of being victims, were eager to point out to proconsular vengeance the manufacturers and workers who had taken the most open part in the resistance.

The guillotine was permanently on the Place des Terreaux, while on the Promenade des Brotteaux the executions were carried out en masse, with cannon loaded with grape-shot.

Jacquard would eventually have been discovered by Couthon's minions if his young son had not thought of running to the military enlistment office and getting two roadmaps, one for himself and the other for One of his comrades, in order to rejoin a regiment marching on Toulon. It was time, for the next day, it is said, soldiers penetrated into Jacquard's retreat. For the Lyons proscribed, a camp became the safest asylum.

The volunteers of the Rhone and the Loire took the road to the South. From the top of the hill of Perrache Jacquard and his son, a little behind their companions, turned round to look once more at the city at their feet. They sought to distinguish, among the hurried waves of the roofs, the one beneath which the mother, the devoted wife, whom they could not but embrace, watched in tears. When would they see her again? They were ignorant of it, and, for one of them, the hour of this meeting was never to come into this world.

Seen from this height, Lyons had, in 93, a strange and gloomy appearance. Above the immense valley there was a smoke, like a funeral canopy, which was not then that of industry. Here and there flashes of fires ... At the rustling of the trades, the noise of a thousand others, emerging from a great city in full prosperity, had succeeded a gloomy silence.

Jacquard contemplated with great dejection this city, the theater and tomb of the dreams of his youth. He repeated mechanically the expressions of the terrible sentence of the Convention: "Lyon is no more!" He has since recounted that, in this crisis of moral collapse, it was his son who restored his courage, expressing the hope that Lyons would survive, despite everything, his epitaph and his executioners.

Their battalion was at first directed to Toulon; But this city, which had opened its doors to the English, as Lyons had yielded to the Sardinians, had succumbed under the blows of the republican armies. The volunteers of the Rhone and the Loire were then sent on the Rhine. Incorporated in the so-called Rhine and Moselle army, commanded by Pichegru, Jacquard and his son took part in the deplorable campaign of 1795. One day charged with the supervision of a number of prisoners in a small village near Haguenau , Jacquard suddenly hears the cannon thundering:

"Companions," said he, "I promise forgiveness and oblivion to those who will go and ask for guns to fight."

All followed, fought, and were pardoned.

It was in one of the unfortunate combats of this campaign, probably that of Heidelberg (October 1795), that Jacquard's son, struck with an Austrian bullet, expired in his father's arms. The pain of Jacquard was immense. After having languished a few months in a hospice, he obtained his leave and set out for Lyons. He found his wife in a granary in the faubourgs, assisted by a generous girl who had devoted herself to her service and who since then remained the friend of the household.

She was still fighting valiantly against misery, making hats of straw on occasion and supported by the hope of seeing her husband and son again.

The interview of the return was both happy and sad. The two spouses "wept together their child, their youth, their fortune, their hopes." (Lamartine)

III

The manufactory population of Lyons had gone through a terrible crisis. In November, 1794, Vandermonde, sent by the Convention to study the means of raising industry in the Affranchie Commune, had found 95,000 souls, while the census of 1791 had found a population of 145,000!

Thus, 50000 Lyonnais had perished tragically or were then fugitives. The revolutionary decree, which assimilated the fugitives of Lyons to the emigrants, was reported shortly afterwards, and a crowd of industrialists, who had settled abroad and prospered there, were seen returning to their native town.

Soon, thanks to the devotion of her children, Lyons seemed to come out of her ruins. Jacquard had returned to work as a simple workman, yet he could not help thinking of the great problem of mechanics which he had been pursuing for so long.

In September 1801, he presented at the Exhibition the model of his first machine, called "the lady-drawers", which earned him a bronze medal, and for which he obtained a patent of invention in the same year. In the statement attached to his patent application, he explained himself in the following terms, on the principle and the advantages of his method.

It is sufficient to vary the dimensions of the machine, according to the number of lakes, in order to easily manufacture all stitched or shaped fabrics, for it is not necessary that the machine be divided into eight parts rather than twelve, sixteen, etc. . It will be remarked, however, that by means of a machine divided into eight parts, it is possible to make the great majority of the fabrics.

The principal movement is the indispensable movement which the worker communicates alternately with the foot at each step.

The motion of the steps must take place independently of the exercise of the machine, and the application of this force to the play of its parts is all the more advantageous, because it suffices to take advantage of an already existing movement.

The manner of putting the machine in motion by means of the steps is a great advantage, since it results in more speed in the execution, for the lakes are lowered at the same time as the steps, while formerly the workman , Having set the steps in motion, was obliged to give the order to draw lakes. "

On December 23, 1801, Jacquard, who had obtained the last bronze medal at the National Industry Exhibition, received from Chaptal, Minister of the Interior, a patent for ten years, which he neglected to exploit . This first trade was still far removed from the object which the inventor pursued with courageous perseverance. Nevertheless, he suppressed the shooter of lakes, as well as an infinity of cords, and he contributed to make known the name of Jacquard. The following year, in fact, the First Consul presided at the Cisalpine Consulta in Lyon, and when he visited the curiosities of Lyons he did not forget the humble Jacquard workshop in the Rue de la Pêcherie at the corner of the Place de la Platiere .

Soon after, the municipal authority granted Jacquard a lodging at the Palais des Arts, at Saint-Pierre, under the condition of instructing young workers without asking them to pay. For two years Jacquard took care of his practical school and the construction of models; He seemed to have forgotten his patent of invention, when he learned that the Arts Society of London had promised a reward of one million to the inventor of a machine suitable for making marine fishing nets. The French Society of Encouragement had put the same question in the contest, offering a medal.

Jacquard, after meditating some time on the problem to be solved, adapted to this new trade a mechanism derived from his first invention. A pedal also gave movement and distributed evenly spaced nodes among the wires mounted on the loom. Dissatisfied with the result, which did not entirely satisfy him, Jacquard neglected to perfect his profession and entirely lost sight of it. But one of his friends, one day discovering the machine in a corner of the workshop, spoke to the prefect of Lyons, who had Jacquard called, and transmitted to the government the results of the tests made in his presence.

Bonaparte, who had already been able to appreciate the genius of the Lyonnais worker, summoned Jacquard and his apparatus to Paris. The inventor cared very little about making an expensive journey to present what he called "a bundle of strings." But the order of Bonaparte was most urgent, and the prefect sent him to a post-chaise at the expense of the treasury.

In his old age, Jacquard liked to relate that he made this long journey in the company of a gendarme, who never lost sight of the inventor or his trade. As a result of the attack on 3 Nivose, the police saw conspiracies everywhere; Poor Jacquard, crossing France alongside a gendarme, must surely have passed for a great criminal and his apparatus for a new infernal machine. He himself was not far from believing himself guilty of some unknown misdeed, and felt very little reassured.

On arriving in Paris, he was taken without debrider to the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers. There, in a room on the ground floor, he was put with his machine in the presence of two men, one of whom was no less than the First Consul himself, and the other Carnot, the organizer of victory.

"It is you," said the latter, "who pretends to do what no man can do, a knot with a stretched thread." Without being intimidated by this sudden inquiry, the inventor set up his trade and made it run before his two astonished interlocutors.

The Society of Encouragement, judging the problem resolved, awarded Jacquard his great gold medal on February 2, 1804, and Bonaparte promised him assistance and protection. It was, indeed, by his orders that the workman was placed, as a boarder, at the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers.

Sure of life and cover, he invented and restored several machines, some for the manufacture of velvet and two-sided ribbon, others for weaving cotton fabrics with several shuttles. The director of the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers, Molard, a benevolent man, a friend of progress, liked to follow Jacquard in his labors, and placed at his disposal his most skilful workmen.

It was then that the inventor found himself for the first time in front of the debris of the Vaucanson weaving machine. The great mechanic had abandoned his trade immediately after the first tests; The weaving machine had been mounted and dismantled many times without being able to make it work, and when Jacquard discovered it, it lay in a corner of the attic, and its rooms were scattered here and there. This discovery was for him a feature of light; After thirty years of research after inventing his "lace-puller" who did not completely satisfy him, Jacquard, at the sight of the draft of Vaucanson, had just conceived the real weaving machine. This moment was for the most beautiful inventor of his life. He forgot his unsuccessful struggles, his pursuit of the elusive idea, he forgot fifty years of suffering, sorrow, and misery; Now he was sure of his success. He made without hesitation the abandonment of all his inquiries, and thought only of perfecting and introducing into practice the combined maneuver of the cylinder and the needles, imagined by Vaucanson.

IV

Jacquard lived happily at the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers, surrounded by the esteem of the learned; But his native city demanded it. Before leaving, he drew from the Gobelins data for the establishment of the charity workshops whose management he was to be entrusted with. He had proposed the manufacture of woolen carpets, the numerous operations of which could be carried out by coarse and novice hands. Jacquard returned to Lyons in 1804, and was installed at the Hospice de l'Antiquaille, where, by means of accommodation and food for himself and his wife, he had to take the direction of the workshops organized in this establishment. He nevertheless accepted this mediocre offer, but which relieved him of the material worries of existence and left him time to work at his craft.

The great mechanic, therefore, occupied himself with his humble industrial education, while appropriating and improving the machine of Vaucanson. At this time the imperial decree dated Berlin, October 27, 1806, authorizing the municipal administration of Lyons to grant Jacquard a pension of 3,000 francs, half of which was reversible on the head of Claudine Boichon, his wife

In exchange, Jacquard yielded to the city all his machines and all his inventions; He was obliged to consecrate all his time and all his labors to the service of the city, and to make it enjoy all his former inventions.

For a pension of 3000 francs!

It is asserted that Napoleon, in signing the decree, said: "There is one who is satisfied with little!"

For this derisory price, the city of Lyons became the absolute owner of the genius of Jacquard. The inventor was to be divided between the workshops of the Hospice de l'Antiquaille and the communal establishments.

Condemned thus to serve two masters, he would necessarily displease one or the other.

"A little too much zeal to work for the factories," Jacquard recounts, "attracted me from the antiquarian administration, which accused me of negligence, and which later made me run away.

On leaving the Antiquarium, Jacquard returned to the palace of Saint-Pierre; He remained there only a few months. The administration of the Museum had informed her that she needed this accommodation, Jacquard then moved to a remote area where rents were cheap.

It was in 1807; At that time, on the report of the learned Thabard, the Academy of Lyon awarded him a medal, founded by Lebrun for a "new mechanism that will accelerate the reform of weaving."

Another success came to devote his efforts. The National Industry Incentive Company had proposed a grand prize for weaving. Jacquard took part in the competition. His machine worked under the eyes of the jury, at the Chateau de Saint-Germain, and won the grand prize. Any other than himself would hastened to exploit his trade in his native town, the more so since the Emperor had granted him a bonus for each of these trades put into operation; But Jacquard was ripening the project of a tapestry factory to be founded at Lyons. He remained some time in Paris, then returned to Lyons in 1808, and began to settle with the help of a few merchants. But scarcely had a few specimens been produced that the merchants withdrew their word; The craft was put under lock and key.

Meanwhile a rich manufacturer of Rouen came to make brilliant proposals to the inventor, if he wished to transport his craft to tapestry. But Jacquard was attached to his native town; Moreover, he was bound by his treaty; The mayor, M. de Satonnay, forbade Jacquard to leave the town. However, his ideas for the manufacture of tapestry were exploited by others with profit; But the complaints of the inventor were in vain and he saw a patent of invention granted to another for his own process.

It was not the only time that his good nature was put to good use.

"So much the better," said Jacquard, "if they have become rich; It is enough for me to have been useful to my fellow-citizens, and to have deserved some part of their esteem.

Meanwhile the workman had found appraisers of his genius and protectors among the first manufacturers of Lyons. Mr Camille Pernon, known for his manufacture of rich fabrics for furniture and draperies (Editor's note: This factory will become the House Tassinari & Chatel) had re-established his factory in Lyon. After the events of '93, the high esteem which he enjoyed among his compatriots had caused him to be sent to the Legislative Body. He was a man who combined with extensive knowledge of manufactures high views.

It was in 1805 that Jacquard addressed himself to Mr. Pernon and talked of his two inventions for the manufacture of nets and for the suppression of lakes. He gave little importance to the manufacture of nets, which was rather restricted in France, but he immediately realized the advantages which could be obtained by suppressing the firing of the lakes.

He promised Jacquard to follow his labors, and charged M. Zacharie Grand, who directed all the labors of his factory, to make trials for putting the new mechanism into practice.

There were then three kinds of crafts for the manufacture of fabrics, and each of these trades required the labor of two persons to make them walk, the weaver and the drawer of ropes.

The most used was the Vaucanson sample craft, commonly known as the Falcone craft; The other two, with samples and hanging, had been perfected by De la Salle, draftsman and painter, inventor of shuttle shuttle (Editor: and the English John Kay, then?). These last two trades served to execute the fine stuffs, remarkable for the height of the drawings and the great number of lakes, which required two shooters, independent of the weaver.

V

Jacquard's first trade, requiring only one workman, was mounted at the beginning of February, 1806, under the direction of Mr. Grand, in the studio of Sieur Imbert, Quai de Retz.

Jacquard had evidently taken the idea of his discovery in a trade with the Falcone of Vaucanson, which walks by means of cartons pushed horizontally by a person sitting at the right of the worker, doing the same function as the rope shooter of the craft ; The reading and the drilling of the cartons belong therefore to Vaucanson.

This great mechanic, who had become inspector of silk fabrics under the ministry of Cardinal Fleury, had announced the discovery of a new mechanism to simplify the trade and to suppress the firing of lakes; But, in the presence of the animosity of the working class, he did not pursue his researches.

It is this ingenious mechanism suppressing the maneuver of the shooter of lakes which is entirely due to Jacquard. By comparing the two apparatuses, placed side by side in one of the Conservatory's showcases, it is believed to be a colossal sketch, next to a complete and finished work.

Jacquard had assimilated the thought of Vaucanson, and had translated it into a more positive and more elegant form. His work, less costly and less embarrassing, produced greater and more precise results owing to the improvement of the mechanism of the needles and of the hooks which replace the tire.

Jacquard still had the happy idea of taking the old square cylinder of Falcon, in place of the round cylinder of Vaucanson. He thus obtained more safety in the play of needles; He could also make larger and more complicated designs by using cardboard strips equal in height to each face of the cylinder and connected by an endless chain.

Under the direction of Mr. Grand, Jacquard brought some improvements to his invention; He mastered and regularized the play of the hooks by elastics, according to the idea suggested to him by a worker weaver named Arnaud. On his advice also, a mechanic worker, named Breton, suppressed the cylinder carriage and replaced it with the mobile spring press which is now part of all the new trades. Jacquard did not apply for a patent of invention for the last type of his trade; He wanted all the workers to benefit from his invention. Jacquard was presented by Mr. Pernon to the Municipal Council and the Chamber of Commerce of Lyon; He found there admirers and protectors; But at the moment when he thought he had conquered the industry of Lyons, he encountered an obstacle which he had not foreseen, the resistance of the workmen.

It was in Jacquard's destiny to wipe in his native town, and from his fellow-citizens, those poor canuts whose injustices, outrages, and even persecutions, which were the lot of many inventors.

This trial was certainly the heaviest of his life; And later, when tributes of gratitude reached him in his retreat from Oullins, from the most distant countries, it was not without a bitter smile that he related the irritation of the workers, their opposition, their malevolence.

One only wanted to see in his original machine a plagiarism, a servile copy of the trades, sometimes Falcon, sometimes Vaucanson.

The Jacquard trade was deemed inapplicable; It was alleged that it worked badly and, as proof, workers exhibited products deteriorated by malice and went so far as to sue Jacquard for damages.

These unfortunate people only wanted to see in the adoption of the Jacquard trade the suppression of all these accessory states of drawing-readers, pairers, makers and shooters of lakes, painful and unhealthy states, but which, however, kept them alive . They contemplated the immediate result without wishing to understand that the prosperity of manufactures, and the very easy and lucrative employment of their children in other labors, would increase their well-being.

It was among them a general clamor, furious, against the perfidious innovation which, it was said, suppressed the workmen, created beggars, annihilated the individual skill of the weavers, and provided the foreign industry with the means of rivaling our industry national.

In one riot, one of the new trades was broken and a bonfire was made of its debris. Another day, on the Quai Saint-Clair, three workmen attacked Jacquard and spoke of nothing less than throwing him into the water. They would have accomplished their crime without the intervention of several people and police officers.

With his fine good nature, Jacquard loved to recount the following anecdote to show how far the blind animosity of his fellow citizens had been:

"One day, when I bought some ropes, my tailpiece came suddenly to pity on his lot and on the diminution of his sale, and I asked him why.

"Ah, sir, it is this damned Jacquard craft which is the cause of it, he has simplified everything, he has taken the poor from the bread. I would gladly give you the opportunity to ...

-All your shop?

"Oh, no, but what would be necessary for that."

"You do not know Jacquard?"

"I do not want to know him." He is a bad citizen; For there is but one evil citizen who can desire the death of the people.

"You have been made blacker than he is, and if he explained to you himself that his profession is all in the interests of the working class!"

"I should like to see how he would do it, the grater!"

-Well ! Listen to me, for I am Jacquard.

And the stammering stringer apologizes.

"It is our wife," he added, finishing, "who tells me every day these wretches."

VI

The inventor of Lyons was to know all the bitterness of human ingratitude and to be called an "unintelligent plagiarist of Vaucanson" before his work triumphed over the ignorance and injustice of his fellow-citizens. It was not until 1809, after four years of struggle, that Messrs. Great succeeded in getting the Jacquard trade adopted by their workmen. Popular resistance had not yet been vanquished when the inventor had the pain of losing the devoted companion of his life, the consoler in the midst of his sorrows and disappointments, and who never despaired of his genius.

In 1812, popular prejudices yielded to the evidence of the facts and there were then 18,000 Jacquard trades in Lyon.

It is fabrics, a specialty entirely in Lyons, in which gold often marries silk, and which can offer designs as pure, as elegant as those traced on canvas by the brush; It was to these rich fabrics that Jacquard had consecrated his machine.

However, the Jacquard trade can be applied to the manufacture of other silks and wool, cotton and even horsehair fabrics. Insensibly, it was adopted in the cloth factories of Paris and Rouen, Birmingham and Manchester; Thanks to him, the manufacture of all the tissues was reduced to the same principle.

After so many vicissitudes and struggles, the age of the great inventor was at least calm and honored, as it deserved to be. He had retired to Oullins, a charming village on the outskirts of Lyons, situated on the banks of the Rhone, opposite the Alps. There, in the little house which belonged to the Academician Thomas, he could blow the northern wind, hear the beating of the innumerable silk crafts to which he had given form, movement, and life. It was his posterity.

He lived modestly in his boarding-house and the fruits of his garden, accompanied by his old housekeeper Antoinette-it would be more accurate to say a friend-who, in 1793, had been associated with the anguish and labors of Jacquard's wife. When she died, the latter had recommended her husband "as a child who would need selves to his last breath."

It was in this retreat that illustrious travelers, scholars of all countries, and statesmen came to visit him, all astonished at the erased existence of the mechanic whose name was known throughout Europe. Sometimes he was dressed as a peasant, watering his vegetables, sometimes surrounded by the children of the school, inquiring about their progress and sometimes inviting them to share his frugal meal, to the great despair of old Antoinette who did not know how Feeding so many mouths.

One day, a sumptuous crew stops in front of the door; The bell rings with a crash, Jacquard himself rushes to open. An English voice is heard:

-Barcon, announce to Sir Jacquard, Lord ...

"I'm Jacquard ..."

"You, Sir Jacquard?" Ah! Very extraordinary.

-Yes, my Lord, in person

And the peer of Great Britain, hat to the ground, stammering excuses, then indignantly indignantly against a country which leaves in the dark a man such as Jacquard.

"What! My lord, "replied the inventor with his simple good-nature," I am satisfied with my fate, I ask no other. "

Indeed, Jacquard was pleased with these testimonies of admiration, but he conceived no pride. Glory had been hard to conquer; It had come so late and after so much bitterness that it had rather brought the old inventor consolation than the forgetfulness of the past.

Lamartine, who has recounted as a poet the life of Jacquard, has drawn from him a beautiful portrait, according to his personal memories.

"He was a man of strong stature, but sinking on himself, by the habit of the labor of his hands, and by the fatigue of the spirit." He had quitted the costume of work, Was dressed in a tunic of leisure cloth, a floating garment with broad folds over his body, and his long basques descending to the heels, his head bent over one of his shoulders, his forehead wide, his eyes broad, his Mouth thick and depressed at the corner of his lips, his cheeks hollow, his complexion as woody as that of the worker who lives in the shade.

A sad and meditative languor was the predominant expression of his physiognomy, either a restraint of mind, or an indelible imprint of the first misfortunes of his life, or self-love long suffering from the inventor who only triumphs late, and when the triumph Is almost identical with the tomb. "

Like all the old men decorated with his time, Jacquard wore the red ribbon with the cross of the Legion of Honor in the buttonhole of his long frock coat to the owner. He had assembled in the salon of his cottage his patents, his machine, and his models, not by a very excusable vanity in an old man who had suffered so much, but because he loved to surround himself with the memories of his laborious life.

Besides, the nobility of character was at the height of mechanical intelligence. He proved his disinterestedness and his abnegation by refusing the advantageous offers of Germany and England, notwithstanding the envious animosity of his fellow-citizens. He waited with the patience of genius for the hour of justice, a slow hour to come, but which, at least for him happier than other inventors, sounded during his lifetime.

"Celebrated," he cried, "sometimes as a man who knows the value of flattery as human insult, in truth, fame is acquired at little expense."

Often, English tourists asked him for an autograph, as a souvenir: "In truth," said Jacquard naively after one of these visits, "these Englishmen are very curious, and it matters whether I know or do not know how to write."

This modest and good man died peacefully on the 7th of August, 1834, at one o'clock in the morning, and his old housekeeper closed her eyes. The next day, a few friends, a very small number of admirers accompanied his remains to the cemetery of Oullins. Mr. Pichard, one of his colleagues from the Agricultural Society of Lyons, recalled in a few words the various phases of his laborious and troubled life.

"The good man, whose earthly remains we entrust to the earth today, was the benefactor of the silk workers of Lyons, by simplifying the craft intended for the manufacture of luxury fabrics, and he was also the benefactor of The city of Lyons, to which he permitted, by his happy invention, to support all kinds of competition in this genre.-He was one of those instinctive men who, without guide or help, trace new paths to industry, New sources of prosperity to the cities, and finally the model of all the virtues ...

To say how perseveringly he succeeded in reaching this immense result, would be too long; His tribulations for the adoption of his invention, would be sad for us who enjoy the fruit of his labors.

Simple and modest, Mr Jacquard received with gratitude the municipal rewards which, although late, surrounded with ease his old age and that cross of honor which decorated the man at the same time that it illustrated the institution ...

He was glad to have been useful to his fellow-citizens, and while Jacquard crafts multiplied, that the name of the inventor became European, he made his fame to be forgotten by gentle virtues. "

And the orator ended by wishing that a public subscription would consecrate, by a monument, the corner of the earth, where Jacquard was resting.

After M. Pichard's speech, M. Grognier, secretary-general of the Society of Agriculture and Utility of Lyons, pronounced a few words of farewell, of which we shall quote only that sentence which summarizes them:

"He was not learned, but he had genius."

His fellow-citizens and posterity were slow to bring to the tomb of Jacquard the just tribute of their gratitude. Six months after his death, the subscription opened by the Conseil des Prud'hommes de Lyon did not exceed 12,000 francs. For its part, the Municipal Council of Lyons had, during the lifetime of Jacquard, had its portrait painted by Bonnefond, to be placed in one of the galleries of the Museum.

On August 16, 1840, in the midst of an immense concourse of curious and admirers, was inaugurated, on the Sathonay place, the statue of Jacquard, due to the sculptor Foyatier.

"The place Sathonay, chosen by the municipal authority, is the most fortunate place," said Mr Fortis, one of Jacquard's biographers, on which is embellished by two fountains and by the main entrance of the garden. Is a market that forms a meeting point for the working population, which mainly inhabits this district.

The statue of Jacquard is 3 meters high: it is raised on a pedestal about 4 meters; The figure of the illustrious worker is a faithful portrait of his features: Jacquard appears to have already passed the age of sixty, his face is full of nobility; He holds a compass in his right hand; In the other, the boxes which distinguish his craft; It combines the piercing for the threads that must pass there: the pose of the statue is perfectly matched to the subject. At his feet are all the accessories proper to characterize him; Tools for the making of the craft, his plan, and a piece of stuffed cloth in which Napoleon's head is remarked. This indicates the time of the discovery. The first tribute paid to Jacquard's memory was the epitaph placed by the Oullins Municipal Council in the village church:

In memory of Joseph-Marie Jacquard, a famous mechanic, a man of good and genius.

Perhaps she would have made the too modest inventor smile; But, to the great confusion of his contemporaries, this simple judgment has been ratified by grateful posterity.

ENDBy Gaston Bonnefon 1931

The life of Jacquard

Joseph Marie Charles dit Jacquard, born July 7, 1752 in Lyon, died on August 7, 1834 in Oullins, is a French inventor, to whom we owe the semi-automatic loom.

I

The traveler who descends the Saône from Trevoux is struck by the beauty, variety and richness of this uninterrupted succession of landscapes, on both banks of which are hills in amphitheatres, covered with vineyards and woods, Hide country houses. He arrives at Lyons, and from the heights of the city his eyes extend to the magnificent panorama formed by the basin of the Rhone, bounded on the horizon by the Mont Blanc, to the eternal ice. This city, favored by the mildness of its climate, the variety of its sites, the abundance of its products, is influenced by the sweet influence of those blessed regions of the South where life is wide, where art is born effortlessly under a Sky always blue, in the middle of a nature adorned with the faeries of the sun.