- Home

- Resurrection ▾

-

Learn ▾

- Free library

- Glossary

- Documents

- Initiation

-

Shaped fabrics

- Introduction

- Popularization

- Definitions

- Le métier de façonné

- Principes du façonné

- Mécaniques de façonné

- Le jeu des crochets

- Les cartons

- Chaîne des cartons

- Mécanique 104 en détail

- Pour en finir

- Montage façonné

- Empoutage 1/3

- Empoutage 2/3

- Empoutage 3/3

- Punching, hanging and dip

- Autres façonnés

- Façonnés et Islam

-

Cours de tissage 1912

- Bâti d'un métier

- Le rouleau arrière

- Les bascules

- Formation du pas

- Position de organes

- Mécanique 104 Jacquard

- Fonctionnement 104

- Lisage des cartons

- Le battant du métier

- Le régulateur

- Réduction et régulateur

- Mise au métier d'une chaîne

- Mise en route du métier

- Navettes à soie

- Battage

- Ourdissage mécanique

- Préparation chaînes et trames

- Equipment ▾

- Chronicles ▾

- Fabrics ▾

- Techniques ▾

- Culture ▾

- Language ▾

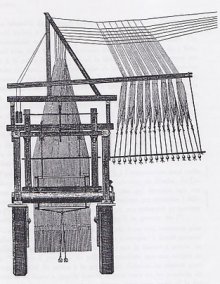

Front view of a button loom

The button loom.

The necessity of satisfying the pressing demands naturally led to the discovery of more expeditious processes of manufacture, better suited also to the execution of common fabrics. In the case of simple decorative fabrics, there was a so-called button loom, in which the draw boy acted directly on the tail cords, by means of lashes and buttons suspended beneath a board fixed on the side of the loom. For the rest the organization was that of the simple looms, but the task of the draw boy was there simplified. It was no more necessary for him to engage in the successive manipulations of the release of the lashes, of the taking of the cords of the simple, it was then enough for him to pull the buttons in turn, in the order assigned to them .

But this simplification had the counterpart to limit the application of this loom to the manufacture of very small sets. The problem of its adaptation to more important tasks was ingeniously solved in the first half of the eighteenth century.

Paulet devotes several chapters to the organization thus created, to which the names of Galantier, Blache, and Talandiers frères remain attached. By the grouping of the cords which had to act on several consecutive blows, the number of buttons could reach 1400-1500, without limiting the interest of this system of loom, to produce half faster.

The organization of a button loom was, it is true, much more complex and costly than that of a loom with a simple ; it had to be able to work for a long time so that the weaver would find a profit. But it procured such conveniences that its use developed alongside the loom to the "grande tire". It was reserved for the execution of fabrics with large drawing and for those where reduction processes could not be applied ; for those, too, where the pull produced only at intervals of several shots, the velvet for example, allowed this loom to weave as quickly as the button.

It is none the less true that the time devoted to the installation of the pens, the time during which the craft was immobilized, the difficulty of correcting errors, the need for the weaver to have at his side competent and skilful assistant, the painful task of drawing, the loss of time caused by the repair of the ropes which broke during work, the imperfections due to the atmospheric influences acting on the length of the strings, and above all, the irremediable destruction of the organization at the end of the weaving, such as the obligation to limit the formulas of the decoration to some genres, had provoked research and aroused achievements from the beginning of the 18th century.

The problem was singularly complex and was approached through differents angles. First, solutions were found to the detail, leaving the arrangement of the tail and the simple, but increasing the possibilities of the loom. Thus its immobilisation with the changes of design was limited only to the making of the lashes, the reading being carried out outside the loom, and then transferred to the simple by transposing pattern. The trial of the new drawings, which took place every season for the preparation of the collection, was carried out without destroying the organization of the little pull (=tire), by the addition of a single to the back of the tail. The excessive fatigue imposed on the draw boys was considerably reduced by the invention of the pulling machine, by which the bending of the tail cords was effected by the depression of a lever acting on two horizontal bars, that one from below passed in front of the simple, that from top behind catches of the lashes.

Then it was the adaptation to the loom of mechanics which made it possible not only to facilitate the pull, but also to retain the benefit of long organization beforehand for subsequent uses.

It is primarily the machine of Basile Bouchon, then that of Falcon, which substitutes plates of cardboard to the lashes of the simple. In this case, the reading consist to the drilling of so many holes in the plates that there would have been cords caught in the loops of the lashes. By presenting and pressing these cardboard strips in front of metal rods, a selection of these stems, the needles, was made through the holes. The pushed needles caused the hooks to hang from the cords of the tail, on the side of the loom. The lowering of the unremoved hooks, those corresponding to the holes in the carton, by means of a treadle, caused the lifting of the threads intended for the production of the decoration.

This was a contribution of decisive importance: the first step towards the substitution of a machine for the tail and the simple. The factory was interested. The regulation of 1744 prescribes that at least one of the six trades to be organized in the office of the Community, in order to subject apprentices, companions and sons of masters to the probationary examination, the masterpiece, must be furnished with this mechanism. Later on, this regulation allows the master to have a fifth loom (instead of four), provided that in the number of said five looms there is at least one mounted according to the new mechanics of Mr. Falcon .

The success of this loom was not considerable ; it nevertheless allowed to weave faster and better and applied to the execution of the fabrics on 400, 600 cords. But the preparation of the cardboard strips was long and costly. Despite the creation of special reading devices, the pitfall of the fast and inexpensive drilling of cartons could not be crossed. It will be necessary to wait until the end of the first quarter of the nineteenth century, in order to solve the problem of reading in and to bring the final solution to the Jacquard mechanics.

At the same time, the idea made its way to entrust to a mechanic, placed under the only control of the weaver, the mission of selecting the threads. By pointing out only as a memorandum the first attempts to create a loom limiting the worker's mission to a supervisory role, the machine of Vaucanson and that of Regnier must be retained, aiming at the suppression of the draw boy. Paulet, speaking of Regnier's cylinder mechanics (this is a creation of a Nîmes manufacturer), says that it is one of the most beautiful inventions ever made since the factory existed and says: I have seen this mechanic, I know it, and if I went to set up a manufactory, I would never use any other than this one to make the common fabrics.

The loom of Philippe de Lasalle.

Having arrived at this point of our study, we must ask ourselves whether this work, in spite of the incessant improvements which had been made to it, could authorize the execution of the very large compositions which Philippe de lasalle was to create. The problem was to bring together an unusual number of lashes. The weft brocade fabric, Lasalle's favorite technique, demands in its application to furnishing decorations, and because of their magnitude, a considerable number of wefts. If no obstacle arose as to the possibility of freely developing the play of these wefts in the whole width of the fabric, it was not the same with regard to their development in height.

There were many means of a purely technical nature, methods of composition, or methods of weaving and reading in, which might limit to a certain extent the number of lashes:

- the marriage of the wefts, a process applicable only to brochures, which consisted in assembling, in the same lashes, catches belonging to different wefts, which the weaver distinguished by specially stitching them.

- the use of masks, by means of which the central part of the superimposed patterns was diversified, by adjusting their composition in the uniform framework of the binding and framing decoration which was made by the same plates.

But even with these cuts, there could be no question of bringing thousands of lashes to a harness. 13,000 in the decoration to the doves, whose ratio is only 0 m. 78 for the width of 54 centimeters; 32,000 for the decoration with the flower basket; 53,000 for that of the kingfisher and it requires larger ones.

Lasalle, therefore, had recourse to removable simples, and distribute the necessary lashes on them. The idea was certainly not new, but it could only take practical form by creating, from scratch, a simple and rapid process of fixing the simples to the harness. Lasalle to discovered this type of attachment ; it is so ingenious that it always surprises us to see it executed, for it is still in this way that we suspend our present days to the machines of stitching and the feet of reading.

Here is what this ingenious creation consists of :On the side of the loom, below a second "cassin", Lasalle fixed a plank pierced with two rows of holes for each horizontal row of pulleys. Each rope of the harness is connected above this plate to a small cube of lead to which a long hook is welded ; the fastening being ensured in such a way that the lugs of the hooks are uniformly arranged along the length of the loom.

At the upper part of the simple, each rope forms a loop, spanning the interval of two straps fixed parallel in a frame ; the number and the spacing of the ruler corresponding to those of the rows of hooks suspended from the cords of the harness. By also matching the spacing of the loops along the rulers and that of the hooks of each row, it is possible, by lifting the frame, to engage a hook between each rope loop and, by a slight longitudinal displacement, to suspend all the loops with the corresponding hooks. In the same way, but by a displacement in the opposite direction, the simultaneous uncoupling of all the strings is obtained.

To take full advantage of this loom, Philippe de Lasalle added the pulling machine. Finally, he created a loom to read and make conveniently the lashes of the simples.

We possess a remarkable description of these inventions in a report presented in 1775 to the Academy of Sciences. It contains a documented comparison of the two systems with detailed descriptions of the loom and the new loom. Philippe de Lasalle had this report published in 1802 for the manufacturers who were not aware of the advantages of his loom could discover them.

The last three phases of the making of a lash.

The lace-maker then disengaged the last leash placed, united in her left hand the two extremities, thus released the selected cords, slid her right hand into the opening and made them pass in her left hand. From the back of her hand she pushed back the strings left so as to be able to grasp the cords taken over the english lashes and slide back the end of the lash. Abandoning the strings of the simple, it formed as many loops as there were holds, the right hand separating them exactly and hanging between each one, the thread to its left hand, so as to leave between the cords and the hand, the length that had to be given to the loops of the lash. The two ends of the thread were then knotted, and the loops equalized and then united, rolling them somewhat upon themselves, and finally fixed to their previously prepared gut cord.

The finished lash were then hung at the top of the simple, and the same operations were repeated for all the other leashes.

The meticulousness of the readings and the preparation of the lashes was extreme because the correction of errors was long and difficult when the simple had risen, disleased and the english lash removed.

The organization of the draw-loom, the preparation of the simple, the lashes, required a long time. Justin Godart, mentions the presentation, in 1783, of a note of expenses incurred by a master worker, according to which the preparation of the simples of his loom required 25 days of readings and 25 days of lashes maker. A state of expenses in 1780 for the preparation of a loom, counts 16 days of reading in and 18 days of confection of lashes for a draft distributed on 12 simples.

The sums to be committed were very large ; ranging from 400 pounds for difficult fabrics, but they could reach 1,500 to 3,000 pounds for the velvet looms for jackets and dresses.

Moreover, all this organization, slowly elaborated, was to be entirely destroyed, the lashes untied to make way for another simple, when the fabric for which it had been undertaken was finished. This was one of the most serious disadvantages of this loom.

So what was this trade capable of ? It had never ceased to be perfected to satisfy the needs of new fabrics, to amplify their decoration, to develop it without repetition throughout the width of the fabric. The number of cords in the tail, originally limited to 300 or 400, had been increased to 800 or 1200. For certain fabrics, especially velvets, tails of up to 2000 strings had been created.

Obviously, it is still the case today, in spite of the improvements acquired, the techniques of the fabrics had to conform to the possibilities of the loom. For example, the need to give the threads individual leases through the heddles prevented the use of weaves which would have led to too many heddles and treadles. This prohibition we find it in the almost exclusive use of brocade wefts, in the use of the threads of the background warp to link the weft effects of the lampas ...

In addition, the manufacture was slow, because it was constrained by the maneuvers of the pull (=tire).

Detail of the layout, reduced toSeventh, decorated with lampas.

Thus, for a draft containing seven colors of weft, for example: one of "liseré" - in the eighteenth century, weft taking part in the decoration at the same time as the formation of the ground texture, and six of weft brocade, the reader selected, in a first pass of the reading, the catches indicated by the color of the border on the little finger of the left hand and, respectively, on the other three fingers the catches represented by the colors of the first three brocade wefts; in a second passage, she picked on three fingers, the catches of the last three wefts.

Having carried out her selection work on the whole width of the simple, the reader was slipping a leash under the cords held by each of her fingers. Having closed the leashes with the receiver cord, she lowered the draft of an interline and resumed its readings, traversing successively each horizontal line and taking into account the interruptions and the repeats of the wefts. The effects of the draft were thus carried over to the simple.

The lashes were built when all the leashes which the simple was to receive were united there. But this work was not always executed in two parts. The lashes could be constructed directly, line by line, as also the reading in could be carried out on a single finger either by the reader alone or with an aid that dictated the catches by following them on the draft.

Making of the lashes.

The making of the lashes required the prior construction of a special lash at the back of the simple ; it consisted of as many distinct curls as the simple had of cords. When all the loops had been carefully equalized, they were tightly stretched in an almost horizontal position. This lash, meaned the english, avoided intercalations of the catches that would have hindered the free operation of the pull (=tire).

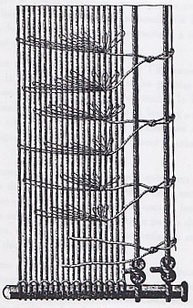

Lashes.The contiguous cords, represented here in isolated loops,were virtually united in the same loop.

To each tail cord was suspended, by a loop or a ring, a new cord, that of the simple. Fixed at the bottom to a stick, they were uniformly taut during work, hanging the stick on the floor of the workshop.

At the simple the lakes were fixed, a group of loops of threads in which were bound the cords of the simple which were to act on the threads of the warp. The problem of the formation of a woven decoration is, in fact, summed up by alternately raising certain threads, for example those below which the weft must appear. Here there were as many loops as there were threads or groups of threads, the "read", to be lifted in the width of the path. All the loops necessary for the passage of a single weft were tied to an extension itself closed with a large rope, the gut cord, charged with maintaining the lashes in their ranks.

On the loom thus organized, the weaving was effected by the simultaneous action of a helper, the draw boy or, more often, the draw girl, and the weaver. By stretching the curls of a lakes, the draw boy released the strings of the simple selected, seized them with both hands and exerted an effort from top to bottom. The corresponding cords of the row bent under this pull; by their extremities connected to the harness cords, they raised the threads grouped in the held eyelets.

It was then that the weaver launched his shuttle after having brought the modifications necessary to the constitution of the two layers of yarn by means of the healds. According to the case, he substituted for the shuttle the figured shuttles of the brocade or the irons of the velvet.

The weaver acted on the heddles by means of steps arranged under the loom. By treading one of the pedals of this kind of keyboard, it caused, according to the mode of attachment, the raising or the lowering of a heald, sometimes simultaneously the raising of a heald and the lowering of another. The treadles, as numerous as the rhythm of the leases required, frequently required the action of the two feet of the workman.

And these operations were constantly repeated; The draw boy sliding down the lash to the bottom of the simple of which he had used, releasing the next while the worker was passing, by the operation of the heddles, the background wefts, those on which no decoration was produced. Then it was, when the time came, a new traction of the cords of the simple, the passage of the decoration wefts...

The length of the tail, which grew to the right or to the left of the loom, depending on its location in the workshop, could be important. Of this length depended the number of lashes which the tail could receive and, consequently, the height of the drawing capable of being executed. The number of lashes which it was possible to collect on a single site was limited. If Paulet points out that he sometimes goes to 1500, it could only be in exceptional cases. Some fabrics required a considerable number of lashes; They were then distributed on several sides, suspended on the tail behind each other, and used in turn. As soon as all the lashes had been fired, the simple was relaxed, its ropes rolled, and it was hung on the side of the tail. In its place was stretched the next simple, and weaving continued from one to the other.

Such an organization does not seem to have been the same at the beginning. First, the lashes were formed on the tail itself and this is how we can still see in action, where the Jacquard mecanic has not penetrated. The visitors of the colonial section, at the exhibition of Paris 1937, were able to follow the operation of such looms at the stands of Syria, Indo-China. The tail is suspended from a frame fixed above the craft where it constitutes the simple prolongation of the harness cords. The draw boy crouching on the loom acts on the threads by lifting the tail cords selected by the lashes, with the aid of a lever if necessary, when the weight to be lifted is too great. This type of loom existed in the eighteenth century, but it could not suit all fabrics because the number of lashes was necessarily limited. It is to increase the number that the tail has been bent on the side of the loom and that the simple has been attached to it.

Organization of the trade, Layout, Layout.

The organization of a draw-loom "à la grande tire", involved two groups of operations; on one hand, those carried out within the loom, and ton the other hand those which must lead to the making of the lashes on the simple.

On the simple suspended on the tail, a preparatory work was first carried out, the reading in of draft lashes, which the pattern drawer had traced on paper set at the scaling down.

The drafts of the eighteenth century differ little from those of our days; The effects which compose the decoration are represented in a more or less conventional manner by means of coloring the small squares or rectangles, constituted by perpendicular lines close together. Each vertical line of this fine grid represents one or more threads, each horizontal line one or more wefts. When the line spacing represents several threads, the leases specific to each of these threads, can not be described in detail, and the draft is limited to situate the forms of the decoration, to delimit them in relation to each other, by indicating each effect by a different color ; for the reading in, the simple was taut, leased, and its cords distributed in a width equal to that of the draft by placing them in the notches of a ruler, the "escalette". By following each horizontal line of the draft, the reader would choose on the simple the cords that would later be girded by the lashes.

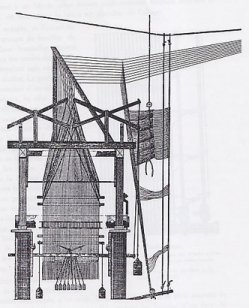

Pickpick, front view

In the previous figure, for the sake of clarity, a single simple cord A was used, controlling the 4 threads G, the first threads of each path of the fabric H. Here we see on the right the pattern composed of 15 threads and on the left we see the 15 vertical simple cords required to control these 15 threads of the pattern. Referring to the foregoing sketch, it will be understood that each of the 15 simple cords will be connected to 4 warp threads.

We have 15 warp yarns and 16 weft yarns making up our pattern on the right sketch. On the left, we have 15 simple cords corresponding to the 15 warp threads, and also 16 lashes (horizontal strings looping on one or more simple cords) corresponding to the 16 wefts.

City of lyonSchool of weavingPhilippe de Lasalle

The draw-loom

In order to give tribute we owe to the man who brought to the Lyon factory the flagship that crowned all the textile production of the eighteenth century, it was necessary to add a few pages to evoke what were the means used at that time for the manufacture of the silk fabrics, to note what the draw-loom was, its long preparation, its functioning, the methods of work and technique which it had imposed, the inventions which, little by little , had enhanced its possibilities. In the contribution to this loom of modifications which transformed his possibilities, Philippe de Lasalle showed his genius. What he created is so perfect that we still use it, hundred seventy years later of distance, in a machine that is the indispensable complement of the current loom, the reading in machine.

To appreciate these inventions at their proper value, one must first look back and study the loom Lasalle had at his disposal for the execution of his first works.

The draw-loom

On the frame of the loom, above the warp, held eyelets, harness cords, arranged as we still see them in our modern arm looms, was fixed a card board, assembling small wood pulleys rigorously arranged in a rectangular frame .In the throat of each pulley a cord passed; inside the loom, these cords were individually joined to the harness cords distributed in the cording board; outside, they were knotted side by side, with a stick fixed to the wall of the workshop. All these cords constituted the tail; It developed laterally at the level of the card board and perpendicularly to the threads of the warp.